I feel doomed (complimentary) to write these posts every few years about rebuilding an online collection. Maybe that’s because they’re always glued together, always better than what came before but simultaneously still a messy bridge between systems. This is by my count the 3rd major new online collection I’ve worked on for the Whitney, on top of an untold number of smaller tweaks and rewrites. Sometimes there’s big new features this enables (see: portfolios, high resolution images, exhibition relationships), and sometimes, like this time, it’s quieter (see: better colors in images, verso titles). I think it’s important to acknowledge this work while also understanding that it is the kind of non-flashy, incremental improvements that are difficult to grab attention for, and despite the evidence hard to always write about.

What we replaced

The last online collection for the Whitney was based on syncing with the eMuseum API, which was connected through a tool called Prism to TMS (The Museum System), our collection database of record. While this was a boon at the time as it allowed us to skip having to figure out the tricky step of how to export data out of TMS and get it online, it was also a drag in that data syncing was brittle and slow. Propagating changes meant syncing each of potentially hundreds or thousands of records over REST APIs each night, and deletions required a long tail of checking whether records not seen in a while had disappeared and should therefore be removed. Getting the difference of “what changed” existed on a spectrum of possible-but-buggy to impossible. At the same time every asset and field had to go through transformations between TMS > Prism > eMuseum > whitney.org, which meant all manner of formatting errors for text or compression issues for images could crop up between each step. It worked, but it had too much middle management.

What we use now

Rather than run multiple entire applications to export data out of TMS, we’ve moved to a small collection of Python scripts that export data as JSON files and images from our shared drives to a private AWS S3 bucket. This choice follows the example of the Menil Collection’s new online collection (thank you Chad Weinard and Michelle Gude for being so willing to share), who recently did something very similar. This approach has the benefit of letting us adjust the scripts ourselves, and made it possible to have both full and differential outputs. This increased the speed and lowered the complexity of the syncing mechanisms for whitney.org. Updates, additions, and removals are easily recorded in nightly JSON exports, and the whitney.org CMS can quickly check for only the changes it needs to make. And dumping everything in a private S3 bucket is ultimately more secure and easier to manage than more web servers running [often] outdated software.

For me the unlock here was realizing that we had basically already written most of the SQL export logic as part of onboarding eMuseum in the first place, and that parsing what I thought of as gigantic JSON files is actually very performant and practically a non-issue. Maybe this is from some threshold of compute improvements over the last few years, or from faster or more prevalent flash storage, or maybe this was just always possible and I needed the suggestion to do it.

The vibe coding of it all

Whatever the enabler, writing Python scripts to export some nicely formatted JSON files is vastly simpler and more controllable than orchestrating multiple 3rd party applications. It’s also easier than ever: navigating complex SQL selections and parsing strange formatting issues are borderline trivial problems to solve with modern LLMs. Outside of the initial direction and some [thankfully still valuable] domain knowledge about TMS and our collections, Claude could nearly write this on its own. Constrained coding problems like this are so effectively handled by AI that it’s almost dismaying to think about how I would have done this 5 years ago.

Unanticipated improvements

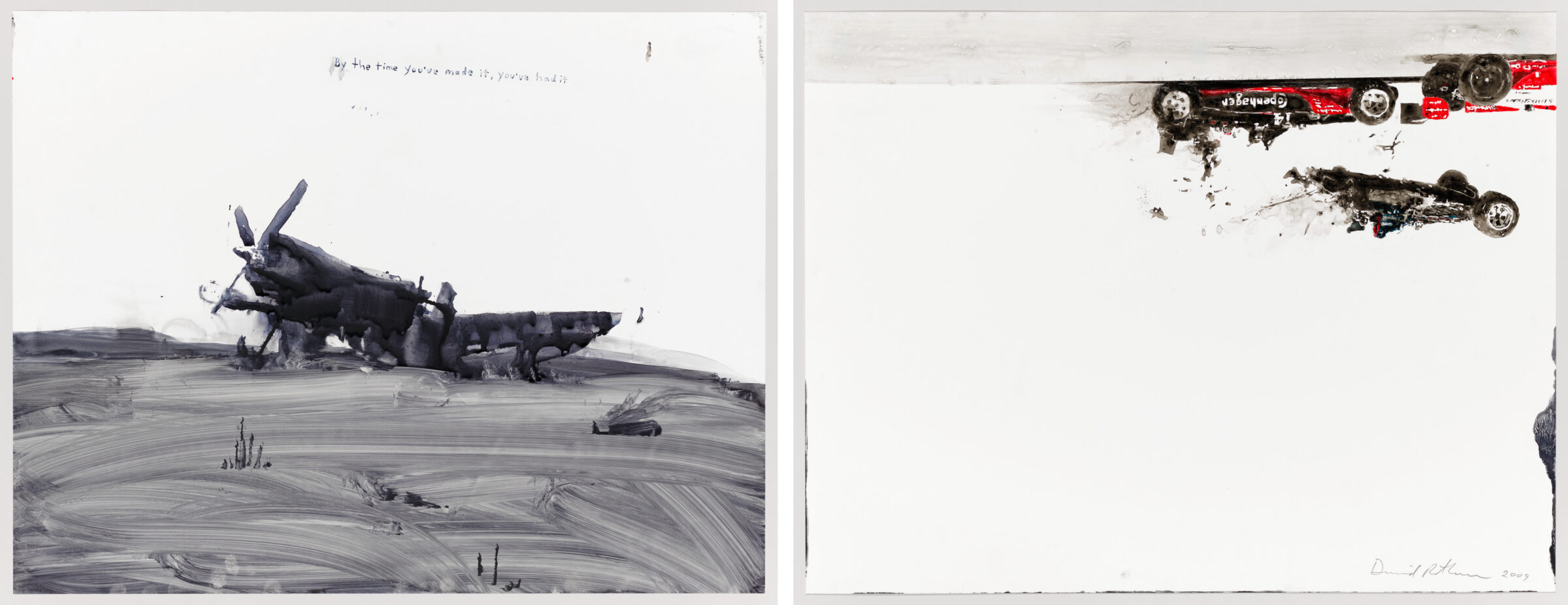

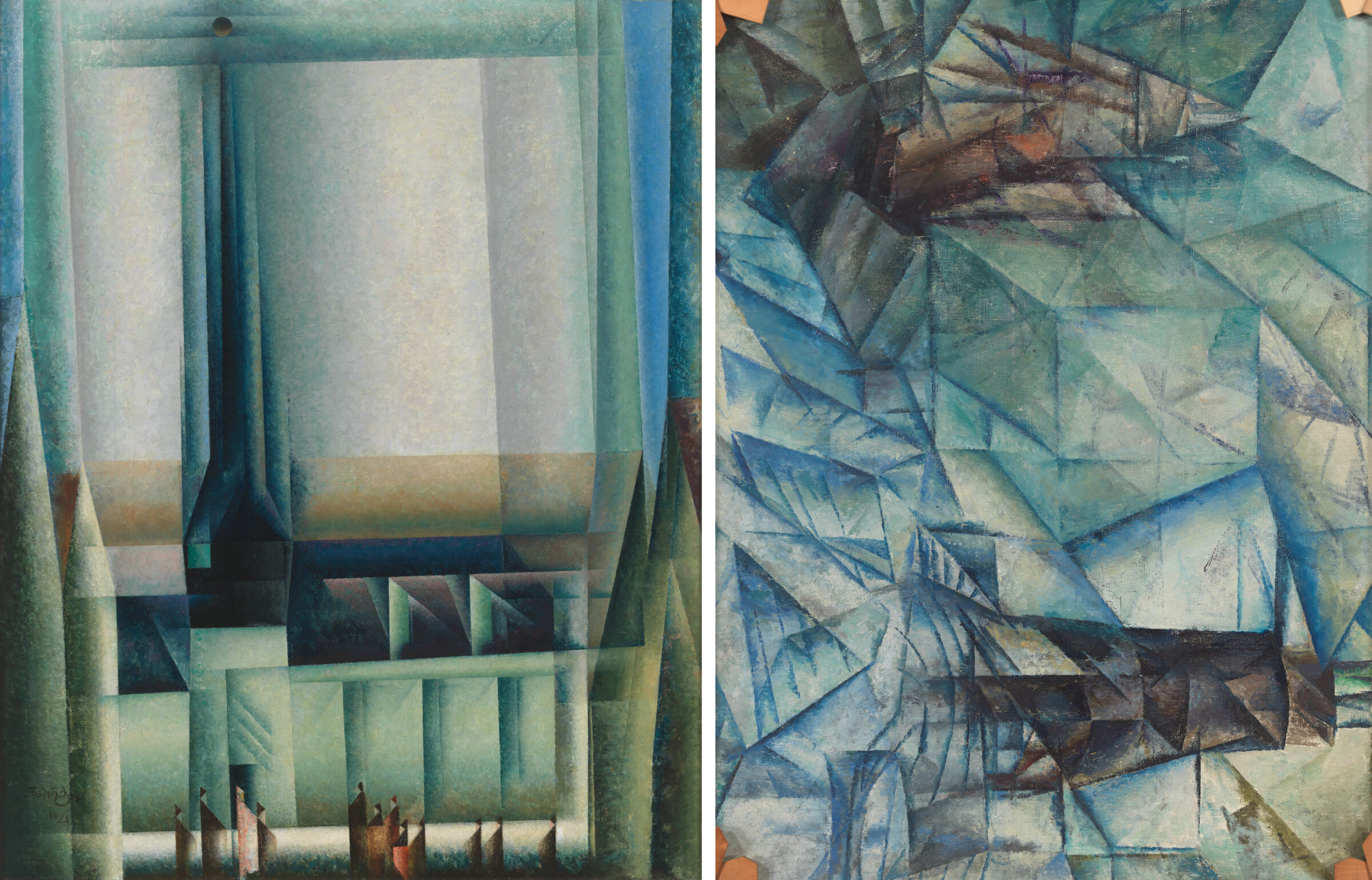

While we started this work due to internal server issues there have been some public-facing improvements I didn’t necessarily expect. For images, removing at least one step of compression in the middle (and potentially an issue with color spaces I never figured out) has led to much better color representation across our collection photography. I didn’t even realize this was an issue until seeing how much richer something like Liza Lou’s Kitchen or Dyani Whitehawk’s Wopila|Lineage looked. In terms of data, in conversations with colleagues it became clear we have hundreds of artworks with reverse sides that weren’t reflected at all on the online collection: neither verso titles, nor images of the verso side, were published. With full control of the data exports it was relatively simple to add these titles to the exports, figure out an appropriate public display, and programmatically add their images. The results can be very cool.

Beyond these changes, there are a number of smaller improvements including:

- “See also” relationships for curator-selected related works, which makes it easier to discover things like studies for final paintings.

- Precise birthdays for many artists, now available on a birthdays page.

- Thousands of new artists online thanks to additional exhibition relationships surfaced through better scripting.

What next?

I’d like to do something with location-level data for exhibitions and illustrate the history of all the Whitney buildings more effectively. Or build some kind of timeline with all the kinds of content we can “date” now. Or set up something with a public MCP server. Whatever it is I hope it’s not another collection rewrite for a while.